Dietary Activism

By Elly Nalbach

December 4, 2017

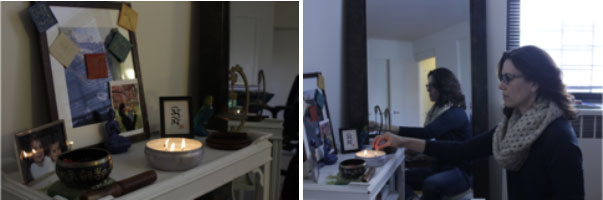

Jenna Hollenstein is a non-diet dietitian and meditation coach practicing in New York. She lives with her eighteen-month-old son, whom she adores, and her partner. Her apartment is filled with books, many of which are well-worn, and toys, also well-worn.

I’ve been a dietitian for almost twenty years. My clients are primarily women anywhere from age 5 to 75, and I practice a non-diet approach to nutrition called intuitive eating. It’s a bit counterculture. The traditional dieting approach to losing weight means going between dieting and binging, and having the pendulum swing back and forth over and over again without progress. If dieting worked, it would have worked by now. Diet culture has programmed us to believe that our bodies are problems to be solved, to the point where, often, the pursuit of a certain body, a certain fitness level, a certain dietary purity, borders on religious.

People who follow the non-diet approach that I practice, on the other hand, shift their allegiance from external things that tell them what, when, and how much to eat, to internal things like hunger, fullness, and satisfaction. They don’t use food as a means of modulating their emotions, and they give themselves unconditional permission to eat, so there’s no black and white, good or bad, dichotomous thinking around foods. My goal is to try to help women make peace with their bodies and to care for and feed themselves in ways that allow them to reach their potential.

I think my desire to help others comes from the realization that a lot of us feel like we need to be different than how we are naturally. Personally, I have always felt like an outsider in my family. I grew up in a household where there was often the message of, “you could do a little better better,” and I always got the sense that I was too emotionally sensitive. Anxiety has played a major part in my life as a result. Even now, my body is smaller than it would be normally because I have struggled with panic attacks over the last year, although meditation has been a huge help.

Through my exploration of buddhism and buddhist meditation, I’ve discovered that some of the qualities that I once thought of as vulnerabilities, like sensitivity, are real strengths. The meditation technique that I practice, which is called Shamata, is about opening to your experience as opposed to removing yourself from it by focusing on the sensation of the breath. It’s transformative—it slows things down, decreases reactivity, and allows me to focus on the things I value instead of the little difficulties in life. It has allowed me to stay sober for ten years, to stay in a relationship, and to be a mom, which has challenged me on every level. I got pregnant 6 months after deciding not to have kids, and raising this child has become an unexpected joy. My goal is to raise him to feel loved and accepted unconditionally, and to help him be a feminist and ally to women.

My work is a form of feminist activism, after all, in that I work primarily with women to help them accept their bodies and treat them with kindness. The amount of energy and time that so many of us put into changing our bodies will not give us the satisfaction that we think it will. In the end, it is the stigma around being in a bigger body and the weight cycling which happens as a result of a binge restrict cycle that independently lead to negative health consequences, not being in a bigger body in the first place. Obesity is not the root of all health evils; wellness is much better defined by genetics, which we have no control over, and health-related behaviors, like eating nutritious foods or doing enjoyable physical active.

Doctors, though, have such firmly set beliefs about fat being unhealthy that it seems like no amount of scientific data to the contrary is going to dissuade them. In order to improve their ability to be of benefit to all patients and not just thin patients, they need to challenge their own personal biases and the biases they were handed in medical school, and explore the data supporting the approach that prioritizes wellness over weight. Doctors, like anyone, need to be willing to step into the uncomfortable arena of what they don’t know and open themselves up to a dialogue with their fat patients, who they have probably been telling to lose weight every time they interact with them as if they haven’t ever heard that before (I use the word ‘fat’ as a neutral term).

One of the things that we can do, just as human beings, is to consider body diversity to be a diversity issue and to understand that we don’t know a lot about a person just by looking at them. We shouldn’t make the assumption that because someone is in a thin body, they are ‘crushing it.’ The evidence shows that being in a bigger body does not automatically mean that someone is unhealthy, and being in a thinner body does not automatically mean that someone is healthy.

As told to Elly Nalbach.