A priest, a rabbi, an imam, and a police chief are working together to create unity in New York City’s “forgotten” borough. In order to live in peace and respect—and curb religiously motivated hate—faith leaders in Staten Island find common ground with law enforcement and one another.

An Attack

On June 24, 2016, during the holy month of Ramadan, a man named Angel Mercado attacked a mosque in Staten Island. Tahir Kukaj, a soft-spoken imam in his fifties, was standing at the front door when Mercado approached. “At first I thought he was late for prayer,” recalled Kukaj. “Then I saw his eyes. He looked lost and full of hate.”

Mercado spit out a threat: “I’ve heard Muslims are here to conquer us. I’m not going to allow that. I’m going to kill you all.” Kukaj tried to calm Mercado down and invited him in for a cup of coffee Instead, Mercado descended the stairs and grabbed a pipe. Kukaj called 9-1-1. He told the members of his congregation who were leaving the prayer service not to touch Mercado. “Don’t do anything,” he said. Mercado came very close but before striking Kukaj, he dropped the pipe and walked away.

Mercado was arrested. The next day, Kukaj received calls of support from the mayor, congressmen, and religious institutions. The NYPD kept the area safe. But not everyone at the Albanian Islamic Cultural Center that he runs was happy with his peaceful resolution. “There are people who say, ‘If somebody comes to your door and attacks you, the law says you are entitled to defend yourself,’” said Kukaj. “But I say, ‘Nobody got hurt. We are not here to punish anybody.’” Weakness, he believes, should not to be confused with peace.

Becoming an Imam in Kosovo

Tahir Kukaj was born in 1965 and grew up in Kosovo, in the former Yugoslavia, as an Albanian Muslim. When he was in fifth grade, his father, Mustafa Kukaj, told him a story Tahir has never forgotten. Twenty years before, the Communist government executed Mustafa’s father—Tahir’s grandfather, who was an imam—and two uncles. As a child, Mustafa made a promise to God: If God spared his life, he promised to send his own son “to study to become like my father.”

Tahir Kukaj wanted to please his father, even if being a Muslim in Communist Kosovo—let alone studying to become an imam—meant persecution. “They were treating imams as an enemy of the state,” said Kukaj. “Even the teachers and educated people of those days had a very negative perception of the imam. My teachers were asking my father, ‘Please do not send him to become an imam.’”

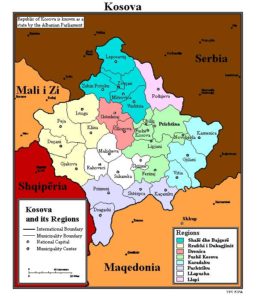

[Credit: MapsSite on Blogspot]

They lived in the town of Drenica, the birthplace of the Kosovo Liberation Army, home to revolutionaries. “My father had all the circumstances around him to be a very violent person,” Kukaj said. But he chose a very different path. Mustafa encouraged Tahir to try and become friends with the people who didn’t like him. Mustafa had no interest in revenging for the loss of his of his own father. “My father, God bless his soul, was a wise man,” said Tahir. “He told us the best thing to revenge your enemy is to make yourself the best that you can be educated. Don’t look what happened in the past, but always build for the future.”

From Azhar University to Staten Island

In 1984, Kukaj moved to Cairo to study at Azhar University, a citadel of Islamic scholarship. He lived with an old Coptic Christian man named Aadil who charged him half of what rent should have cost. He told Kukaj to pay him what he could afford, and he would get the rest from God. “Aadil—that name—means ‘just’ in Arabic, and he was just,” Kukaj said.

Kujai earned his PhD from Azhar University, mastered Arabic, and read widely. One of his professors assigned the class to read the Bible. “He said, ‘Read it with the same respect that you read the Quran,’” Kukaj recalled. “There were so many stories repeated.”

Most religions, he says, occupy common ground. “Teachings of Abrahamic faith—we are 90 percent the same,” he said. “Respect for life. Equality. The life of one human being is equal to all of mankind.” Regarding the fundamental tenants of faith—the religious texts—everyone should agree, Kukaj said. “But there’s an expression in Arabic that says the devil lays or stands in the details. When we go to cultures and traditions, these are man-made. Religion does not have ethnicity. It’s a conviction. It’s a matter of choice. Tying religion to a certain race—this is another part of the details—the devil—that put nations against nations.”

In 2002, Kukaj became imam and director of outreach at the Albanian Islamic Cultural Center in Staten Island. He has followed his father’s advice and made friends with people of different backgrounds, ethnicities, faiths, and cultures.

2017 Mid-Atlantic Catholic-Muslim Dialogue, sponsored by the Islamic Center of North America and the Archdiocese of New York

On October 9, at the Knights of Columbus in Staten Island, fifteen Catholic and Muslim leaders, including Imam Tahir, sat around a conference table and talked about their faiths. Two people—one Catholic, one Muslim—made presentations on the role of Abraham in their respective religion, then everyone discussed their interpretation of the same man’s legacy. That night, they ate dinner together in the banquet hall of the Albanian Islamic Cultural Center. The NYPD and other members of the faith community joined.

“I love to eat,” said Father Brian McWeeney. “I will confess I love to eat.” In his ecumenical work, he has found food is the best way to bring people together. “You cannot get too angry with somebody who just gave you a turkey dinner,” he said, adding cheerily, “as long as it’s Halal. You have to begin to say, ‘Hey, this guy, this lady—they are good people.’”

Father McWeeney introduced Detective Mohamed Amin of the NYPD. “Here in New York,” Amin said, “we represent every part of the world. Probably 200 countries represented, with 160 languages spoken in the city.” The NYPD is a reflection of the city’s diversity, he said. “I am a proud Muslim. My partner is Catholic. My supervisor is Jewish. We work together as one.”

Rabbi Judah Newberger gave the closing prayer and directed it at the diverse crowd. “The most beautiful prayer,” he said, “is just looking out on you.” He continued, “Lord God, give us the strength to persist in our convictions because we know that in coming together as human beings, and emphasizing only the positive—that which unites us, that which reflects your love, your graciousness, your compassion and your justice—that we are surely on the right road.”

The next morning, Catholics and Muslims met again. For lunch, they ate traditional Albanian pizza. Father Brian said he regretted that their dialogues didn’t get much press. “If one of us had brought a knife and stabbed someone,” he said, “we would get a lot of coverage. It would be on the front page of the New York Post. But if nothing bad happens, there will be no stories.”

Bishop O’Hara agreed. “I’ve always believed in good news,” he said. “Unfortunately good news, I guess, doesn’t get ratings or sell papers.” But he believes “something great is happening in Staten Island.” He quoted Father James Keller, who founded the Christophers: “It is better to light one little candle than to curse the darkness.”

Building Bridges Coalition of Staten Island

On October 24, at the Jewish Community Center in Staten Island, high schoolers and senior citizens gathered for a dialogue on belief, practice, and faith. Buddhist, Catholic, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, and Protestant clergy sat on a panel together. The theme of the evening was, “What is the meaning of America today?” Imam Tahir sat on stage between Rabbi Newberger and a nun. The audience was asked to write down a question on a note card. The question could be addressed to one person of the clergy, or the whole panel. Questions inspired the conversation.

“For a human being, it doesn’t matter what religion or race or gender he is,” said Imam Tahir. “Everyone would like to have a nice, decent life, to be respected, to be loved, and to be welcomed.”

Interfaith Prayer Service sponsored by the New York City Mayor’s Office and the NYPD

On November 9, close to one thousand people filled the Albanian Islamic Cultural Center in Staten Island. Speakers included:

Bishop Victor Brown, Mt. Sinai United Church

Reverend John Carlo, Christian Pentecostal Church

Reverend Demetrius Carolina, First Central Baptist Church

Reverend Maggie Howard, Stapleton Union AME

Monk Bhante Kondanna, Staten Island Buddhist Vihara

Rabbi Mendy Mirocznik, NY Rabbinical Alliance

Dr. Ram Nair, Staten Island Hindu Temple

Bishop John O’Hara, Archdiocese of New York

Reverend Jennifer Richards, Trinity Lutheran Church

Reverend Terry Troia, Project Hospitality

Imam Tahir Kukaj, Albanian Islamic Cultural Center

Assistant Chief of the NYPD Edward Delatorre

Commissioner Marco A. Carrion, Mayor’s Community Affairs Remarks

Chief Delatorre said that, when he was in high school, he always wanted to travel the world to meet people of different backgrounds and religions. When he looked out to the crowded mosque, he saw that world in front him. “The language might be different. The accent might be different, but at the core of what we’re saying and what we believe in—it’s all the same.” He was proud that high school students made up part of the crowd. “This is your world,” he said to them. “How you view it is so important.”

Tahir said that, in addition to bringing together religions, the event showed “support to the NYPD, for the heroic job that they do, especially during these times that our city is a mecca–a target for those who would like to have joy and good time.” “New York City,” he continued, “is capital of the world. It’s also a place where evil people would like to be in any way they can. NYPD is doing a tremendous job in keeping us safe. As a community, we want to show our support and gratitude.”

Solutions are Simple

According to a study by the Pew Research Center, assaults against Muslims in the United States have surpassed already high 2001 levels. In 2016 in New York City, 183 hate crimes motivated by religion were reported to the FBI.

Kukaj recognizes that Islamophobia, along with a spirit of anti-immigrants, exists. “Me, as a white Muslim, I don’t have much of a problem,” said Kukaj. “But other Muslims, of different races—especially when they wear certain attire—they have some hard time.” Kids in school are bullied, and their parents come to Kukaj for guidance. “I see the parents crying,” said Kukaj. “They don’t know what to do. As an imam, as a human being, when I see somebody who is desperate and needs help, and you cannot do much except for praying for him—it’s not easy.”

But Kukaj doesn’t dwell in desperation. He wants people to know that solutions do not have to be complicated. Strangers, he says, just need to be good to one another: “All that it takes is just a tap on the shoulder and to say, ‘Listen, I like you, guy. You are a good New Yorker. You are a good American.’ That will make the world to him,” said Kukaj. “In our tradition, Islamic tradition, even a smile to the face of a human being is a charity.

[For more information on interfaith efforts in New York City, you can visit the Interfaith Center.]