Story by Katherine Ellen Foley

Cover art by Steph Yin

—

In a sense, we’re all just vessels for viruses.

As you read this, you are probably carrying some kind of virus, even if you’re not feeling sick. There’s a good chance you’re playing host to a strain of the common cold or flu, but as long as you’re healthy overall, you won’t even suffer a stuffy nose.

When we do get sick, most of the time our bodies can fight off these infections in a few days. But alas, sometimes there are infections we can’t shake — ever. These are the viruses that are able to go latent in our bodies. Without disturbing us, they lay in wait for the right moment when our defenses are down, and come back in full force.

Viruses with the ability to go latent are relatively common, and most of them aren’t too much of a health concern. Consider chickenpox, a virus so common in kids it’s almost like a rite of passage. Symptoms include telltale itchy pox and a fever, and usually leaves us unscathed. Later in life, though, it can cause shingles, a painful outbreak of sores on our skin. Chickenpox and shingles are both caused by the same strain of a kind of herpes viruses (and there are vaccines for both).

The idea of herpes may evoke thoughts of a sexually transmitted infection, but there are eight strains of this virus, the most common of which is called herpes simplex one (HSV1). This virus causes cold sores, also known as fever blisters, on either your lips or genital area. But even though as many as 90 percent of adults have HSV1, most people don’t have cold sores all the time: This virus spends most of its time latent.

So just how does HSV1 conduct its disappearing act?

So just how does HSV1 conduct its disappearing act?

HSV1 can move from our outer layer of skin to our nervous system, according to Jay Brown, a microbiologist at the University of Virginia. When we’re first infected with the herpes virus, we may have an outbreak of cold sores as the virus infects the cells on our lips where it “replicates like crazy,” said Bryan Cullen, a microbiologist at Duke University. As the virus makes more and more copies of itself in our skin, we get lesions that look like fluid-filled pimples that itch and burn. After a few days to a week, these lesions disappear and leave us blemish-free. But that doesn’t mean that the virus is gone from our bodies.

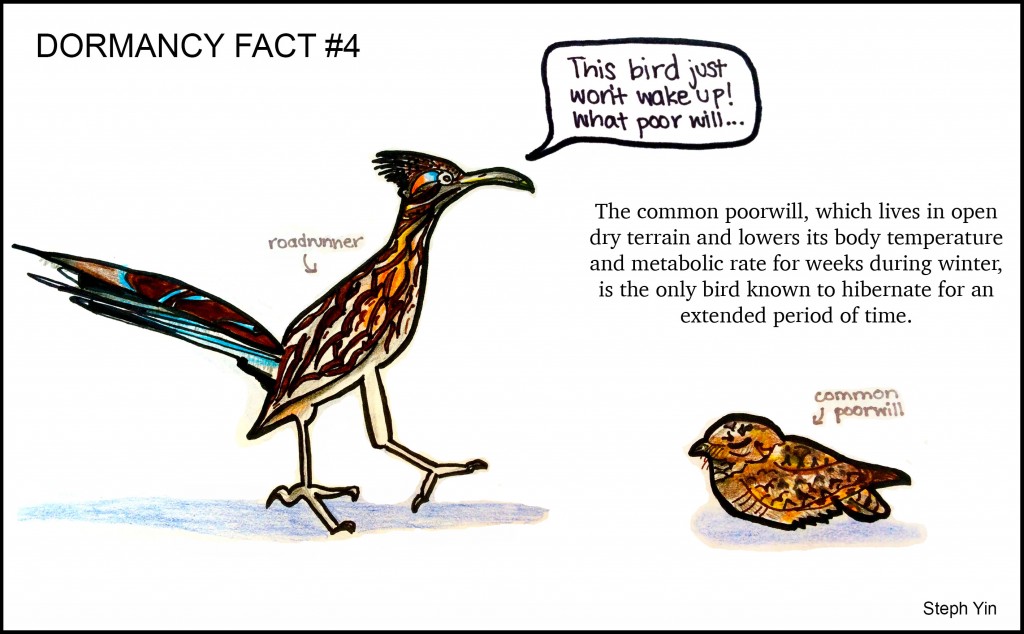

While the superficial lesions heal, the virus crawls (“herpes” likely came from the Greek word herpein, “to creep”) up the nerves in our lips to a bundle of neurons called the trigeminal ganglion. We have two of these groups of nerves located near each temple; they control the feeling and muscle movement in our faces. For reasons not entirely well understood, it stops here, and doesn’t go any further. Like a bear entering hibernation, the virus discontinues pretty much all of its usual daily activities: No more reproducing, or making much of anything for that matter.

“They actually don’t produce any proteins at all during latency,” Cullen said. “The virus sort of down-regulates its own ability to reactivate.” It produces RNA, a type of simple genetic material, but this is likely to make sure it stays otherwise inactive. It’s just waiting for the right moment to pounce.

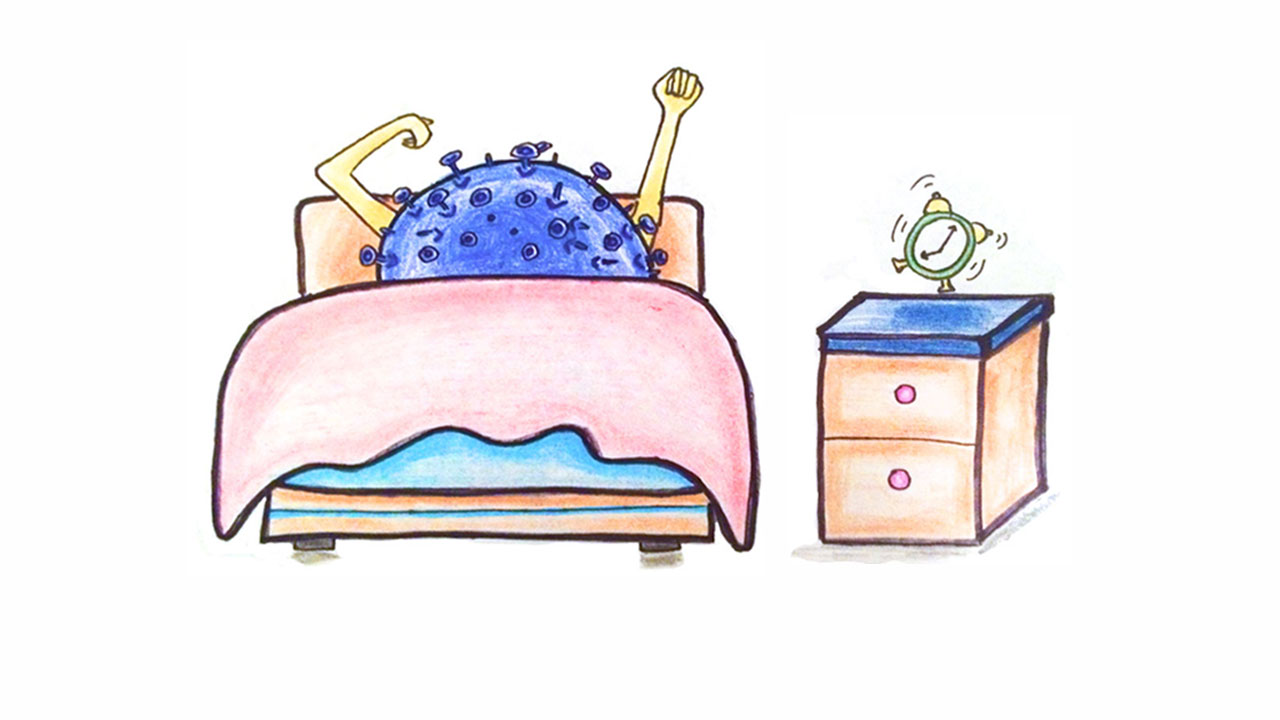

It’s hard to predict when HSV1 will wake up (there isn’t a good animal model for studying it just yet) but when it does, it’s annoyingly obvious. The cold sores on our faces re-appear, angry as ever — probably at an inopportune time. Cullen and UVA’s Brown concur that physical and possibly emotional stress is a key factor driving repeat outbreaks. Something like a fever, sunburn or even a major presentation for work can restart the virus’ engines. It can then inch back down our nerves to infect the same skin cells near our mouths.

If you do have a fever blister, it’s important not to share drinking classes or utensils, and kissing probably isn’t the best idea: HSV1 can jump to a new host just from contact with skin. Some people experience frequent repeat outbreaks, while others may never experience one again.

Fortunately, this virus isn’t life-threatening in most healthy patients: It’s more of a cosmetic annoyance than anything. A few days after the virus reemerges and erupts on our faces, it returns to laying in wait in our bodies, hiding from our immune systems, waiting for the right biological trigger to become active again.

“The ideal thing the virus wants to do is grow and get passed on to the next host,” said Brown. He says most viruses don’t want to kill the host; the host has to stay alive so the virus can keep replicating. They just want to move on to the next one to keep their cycle of life going. So though we may think of ourselves as being evolutionarily superior with our multiple cells and organs, to a virus, we’re just a big vehicle passing them along from one host to another.