Olga Nuñez was 18 when her mother moved the family from Guatemala to the South Bronx. Like many immigrants, her family arrived in America with very little but high hopes. Her family was part of a wave of immigrants, who lost their livelihood with the collapse of the fruit market in Central America.

Once in the U.S., Nuñez’s mother found a job working long hours at a garment factory. The family had found economic stability and Olga found something she thought she left behind in Guatemala: her fellow Garifuna.

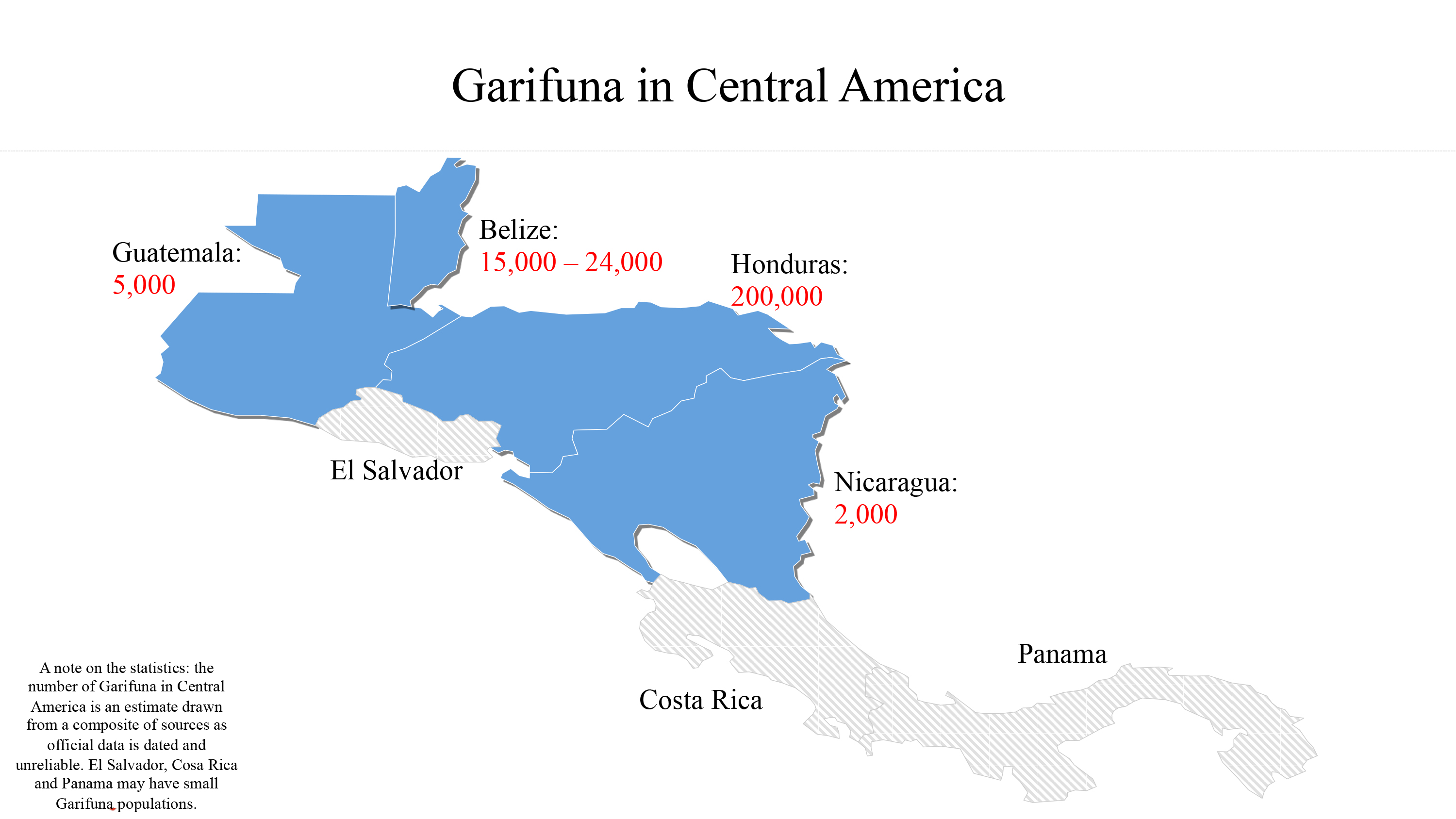

Nuñez, now 42, is a descendant of a community of Afro-Caribbean and Arawak peoples from Central America’s Caribbean coast. The Garifuna trace their origins to West African slaves who were expelled by the British from the island of St. Vincent in the late 1800s. Following an uprising against the British in 1797, the British resettled the Garifuna on the island of Roatán, off the coast of Honduras. Over time the community spread, establishing villages in Belize, Nicaragua, and Guatemala.

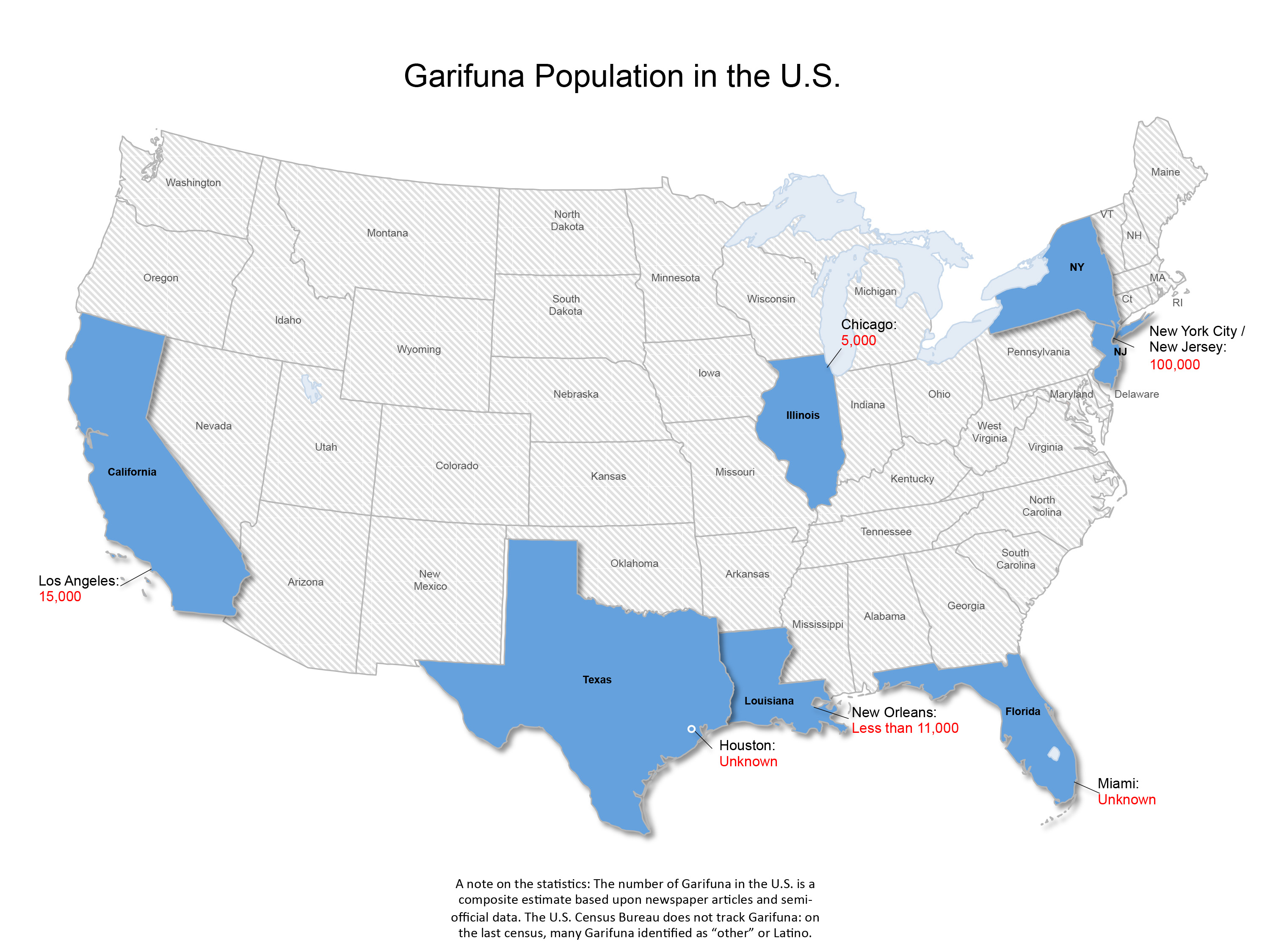

For much of the 20th century, Garifuna immigrants have fled poverty and violence in their home countries to settle in America. Many travel through harrowing conditions to find their way to New Orleans, Texas, Los Angeles, and New York, where they historically found work on ships.

Migration has fostered a strong sense of identity. Garifuna celebrate their own unique heritage and language through music, which is characterized by guitar and drums, as well as religion and food, including Hudut, a coconut-based shellfish stew served with mashed plantains. Dance is an especially important part of the Garufina culture. Garifuna men and women dance together to for a variety of occasions, including birthdays and deaths.

In the U.S., Garifuna are often assumed to be African-American, because of their skin color, or Latino because many speak Spanish. Many Garufina in America do not speak the Garifuna language—which has bits of English, Spanish, French, and Arawak. Garufina leaders in America fear the language may one day soon disappear.

To preserve their culture, local leaders in New York City have encouraged Garifuna to list their heritage for the US census, and have pushed authorities to create a “Garifuna” category. On Saturdays local educators offer Garifuna language classes in the Bronx. And a local blogger from the Bronx, Teofilo Colón, has launched the website “Being Garifuna” to document community news.

Nuñez herself remains a fierce advocate of Garifuna culture. Once a week she dances with a troupe in a South Bronx auditorium, and once a month, she sings in a Catholic mass, partly in Garifuna.

By Christopher Crosby