The History of the Gowanus Canal

The remnants of the past can be seen in the old warehouses and vacant lots that line the banks of the Gowanus Canal today. These structures represent a long forgotten history of the once flourishing industrial neighborhood and the huge role it played in the rise of New York City at the expense of its own ecological health.

“Anything negative you can find about the New York harbor in general has happened in really concentrated form in the Gowanus Canal” – Biologist John Waldman

What has happened to the Gowanus is similar to the larger history of the New York Harbor into which the canal feeds. The dramatic population and business growth that occurred in the Gowanus and the surrounding neighborhoods mirrors the same trends that swept Manhattan and other parts of the city years prior. The New York Harbor experienced very similar abuse and contamination up until the mid-twentieth century.

But while the Clean Water Act of 1972 brought about the eventual revival of the New York Harbor, it did not have the same impact on the Gowanus Canal. This federal law outlawed dumping pollutants into the New York Harbor but it also caused most of the remaining industrial business along the canal to hit the road, leaving it virtually untouched for decades.

In 2010, the EPA designated the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site, the latest chapter in the waterway’s polluted history.

1600s

1849

1869

Early 1900s

1911

1941

1972

1999

Early 2000s

April 2009

March 2010

Dutch explorers arrived and began to settle in present-day Brooklyn, including the area that is now Gowanus. The land was situated around a series of creeks – an inlet of small waterways among fertile saltwater marshlands, brimming with ecological life. Oysters collected here were Brooklyn’s first export to Europe, and were supposedly the size of dinner plates. The Dutch settlers decided to name “Gowane’s Creek after Chief Gouwane, leader of the local Canarsee tribe who were living along the shoreline.

As more settlers arrived in Brooklyn, the neighborhood surrounding Gouwane’s Creek grew; gristmills and other industrial sites were established along the shores of the creek.

Eventually, those in business along Gouwane’s creek recognized a need for larger docking and navigational facilities in order to sustain the ongoing industrial growth, which would raise property values and bring more people and businesses to the area.

The New York Legislature authorized the construction of the Gowanus Canal.

The construction of the canal was completed. Financial and technical limitations ensured inherent design and construction flaws from the very start; the canal’s dead-end design did not facilitate water flow, as it was mistakenly thought that the tides would be sufficient enough to create significant movement.

At the time though, the modified waterway welcomed more settlement and more maritime and shipping activity, helping to bolster the economic flow between Brooklyn and Manhattan through the New York Harbor.

Throughout the rest of the century, a thriving industrial center developed around the Gowanus Canal as factories, warehouses, oil and gas refineries, and more sprang up in the new economic hub of Brooklyn. Millions of tons of cargo were produced and trafficked along the canal each year.

In fact, most of the characteristic brownstones that line the streets of Brooklyn in Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill and Park Slope, to name a few neighborhoods, were constructed using the barge service that carried in materials from New Jersey and upstate New York through the canal.

The surrounding neighborhood industrialized as well. Chemical plants, coal yards, mills, shops, manufacturing plants, tanneries, and more opened their doors…and conveniently emptied their waste in the canal.

At it’s peak in the early 20th century, the Gowanus Canal had more than fifty industrial business along its shores and tens of thousands of vessels travelling through the waterway. In fact, between 1915 and 1950, the canal was deemed the busiest commercial canal in the country.

The intense industrialization and rapid population growth in Gowanus overwhelmingly strained the local infrastructure. This resulted in a poor sewage system that dumped 40 billions of raw sewage into the canal annually, combined with ever-increasing amounts of industrial pollutants. Health workers found diseases such as malaria and typhoid fever in the water.

These problems were not necessarily singular to Gowanus. By the turn of the century, thriving population growth in all of New York City raised important questions about urban development and waste water sanitation, which leaders had clearly not been equipped to handle. All of the pollutants from new and nearby buildings, as well as all the sewage from surrounding neighborhoods drained downhill, into the Gowanus Canal. The canal had to be regularly dredged by the US Army Corps of Engineers to keep the waters navigable by large vessels.

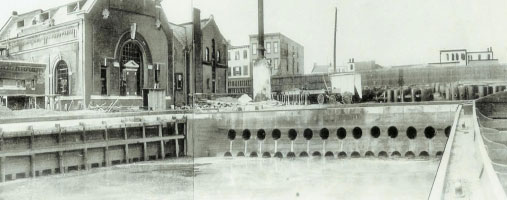

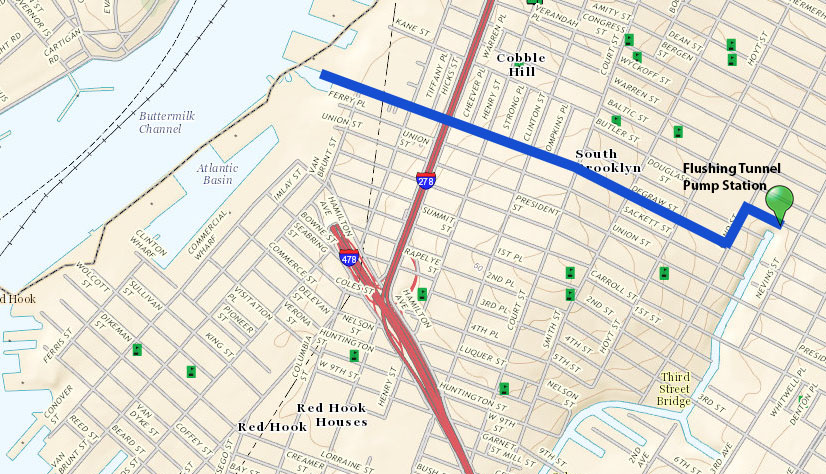

The city of New York installed the Flushing Tunnel at the head of the Gowanus Canal. The tunnel pumped waters from the nearby Buttermilk Channel into the canal to create a flow which was designed to move stagnant polluted waters out of the canal. However, the weak tunnel suffered numerous malfunctions and operational glitches.

Robert Moses completed construction of the Gowanus Parkway (eventually known as the Gowanus Expressway), just one example of the infrastructural shift taking place in Gowanus as the development of cars and trucks rendered maintenance of the canal and its barge service unnecessary.

As the city’s industrial centers moved inland, the Gowanus Canal was increasingly neglected, used mostly as an ominous dumping ground. The impetus to maintain the canal’s functionality severely diminished.

Shortly after the US Army Corps of Engineers dredged the canal for last time in 1955, the Flushing Tunnel’s propeller shaft broke down. Despite public pressure, the repairs were put off and the canal returned to its stagnant, polluted state.

The federal government passed the Clean Water Act, which severely restricts the types and amounts of pollution that are allowed to enter America’s waterways.

[huge_it_videogallery id=”3″]

The community in Gowanus and the surrounding area called for the local and state governments to do something about the terrible conditions in and around the canal, urging them to use the full power of the Clean Water Act to counteract the current environmental conditions.

The city finally responded to public pressure and the Flushing Tunnel was reactivated. Fortunately for residents, the foul odor that once emanated from the canal’s banks has subsided since then. However, decades of damage has taken its toll on the canal, whose bottom is lined with a layer of sludge containing heavy metals, PCBs (a chemical pollutant emitted mainly from older electrical equipment) and other toxins.

Just as the Gowanus Canal was becoming a more friendly atmosphere in the absence of such stinky stagnation, a growing development fever started making its way to the surrounding neighborhoods. Real estate developers – residential, manufacturing and commercial – began to venture on to the long-abandoned shores of the Gowanus.

The Environmental Protection Agency issued a proposal to designate the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site, which garnered a mixed reaction from the community. Some welcomed the federal clean up, others strongly opposed the imposition, including many city leaders arguing that a Superfund designation would stigmatize the neighborhood in the eyes of potential residents and developers, which would stunt the growth and vibrancy of Gowanus. Furthermore current mayor Bill de Blasio, who was a city councilman at the time, was reported to have expressed severe skepticism at the ability of the Superfund program to acquire its funding, in favor of a cleanup plan sponsored by the city. Though up to that point, no formal clean up effort had taken place.

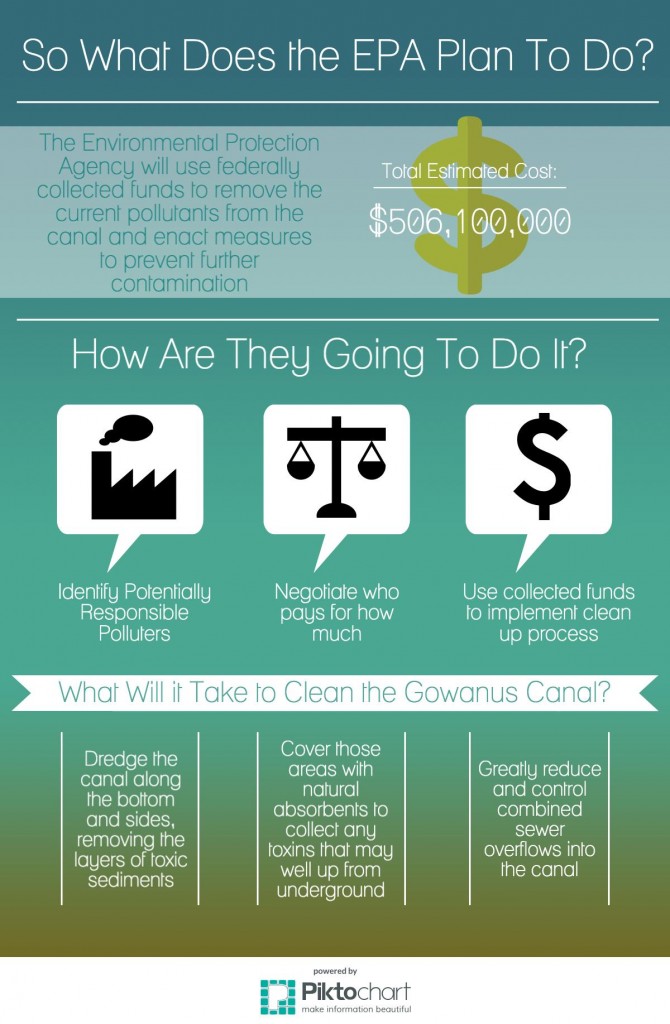

The Gowanus Canal is formally designated a national Superfund site.