By Shannon Hall

—

From New Mexico to British Columbia, the Rocky Mountains stretch high into the sky, their snow-covered peaks embracing the brilliant blue. But where they cross northern Wyoming, a huge chunk is carved from the rugged range. Within that circular basin, there are no sheer walls, steep couloirs or craggy peaks. Instead, there’s a gaping hole, a caldera, in the Earth — the result of an ancient supervolcano.

The “hot spot” responsible for the Yellowstone caldera has erupted dozens of times. Although the last eruption occurred hundreds of thousands of years ago, the supervolcano is far from dormant. Today, a monstrous plume — with enough hot rock to fill the Grand Canyon 14 times over — carries heat from deep within the Earth’s core to Yellowstone’s surface. Where the plume emerges, it transforms the earth into an alien landscape.

Not only is the supervolcano still very much alive, the land above it is literally boiling over.

Unnamed Geyser

More than 10,000 hydrothermal features dot Yellowstone National Park, drawing over 3 million tourists each year. The geysers, hot springs and fumaroles change their behavior constantly, popping up in forests, unexpectedly melting paved roadways, and spewing clouds of steam high enough to spot from an airplane.

Steamboat Geyser

When geysers erupt they can send steam and hot water hundreds of feet into the air, release a frightening screech and even the smell of rotten eggs. But what exactly triggers these eruptions? It likely comes down to a series of loops and side chambers that branch off of a narrow channel connecting an underground reservoir to the surface. These chambers can easily trap rising bubbles of steam. And with enough steam trapped, water starts to boil from the top of the column downward, triggering a full eruption. It doesn’t take long, however, before the geyser settles back down and the hidden cycle begins again.

Old Faithful

Although geysers continue to baffle scientists, some are incredibly predictable. Old Faithful erupts every 65 minutes after an eruption lasting less than 2.5 minutes, or every 91 minutes after an eruption lasting more than 2.5 minutes. (Okay, so there’s a margin of error of 10 minutes, but that’s pretty impressive for Mother Nature!)

Excelsior Geyser

In the 1880s, the Excelsior Geyser (tucked in the northwest corner of the park) erupted in bursts 50 to 300 feet high. The eruption was so violent that it seemingly ruptured the geyser’s underground systems, transforming the geyser into a silent spring. That is, until Sept. 14, 1985: Then the geyser roared back to life with 47 hours of major eruptions. Today, it’s back to silently churning hot water from its volcanic depths.

Mustard Spring

Unlike geysers, water from hot springs flows unobstructed. These bubbling cauldrons can easily be hotter than 150 degrees Fahrenheit in their centers. Because there’s very little living there, the water is a clear, deep blue. But as the water spreads out and cools, it creates concentric circles of varying temperatures where different types of bacteria live.

The Emerald Pool

Synechococcus — a particular type of photosynthesizing bacteria — live in the outermost band. Although the primary color of photosynthesis is green, which comes from a chemical called chlorophyll, it can easily be surpassed by accessory pigments known as carotenoids, which are red, orange and yellow. So the same pigments that transform leaves every autumn are responsible for Yellowstone’s gorgeous colors.

But no hot spring compares to the Grand Prismatic Spring. At 370 feet in diameter and over 121 feet deep, it’s the largest in the park. “Nothing ever conceived by human art could equal the peculiar vividness and delicacy of color of these remarkable prismatic springs,” wrote Ferdinand Hayden, an early explorer, in 1871. “Life becomes a privilege and a blessing after one has seen and thoroughly felt these incomparable types of nature’s cunning skill.”

Mammoth Hot Springs

Although most hot springs are well contained within their colorful pools, some can slip beyond their borders. Mammoth Hot Springs (which is actually north of the Yellowstone caldera) is the result of multiple springs gurgling down a hillside over thousands of years. Along the way, its hot waters deposit calcium carbonate, the main component of eggs and snail shells.

Biscuit Basin

In such an extreme environment, bacteria thrive while trees strive to stay alive. If a new hot spring pops up in the middle of a field, its vapors alone have been known to kill grazing bison on the spot.

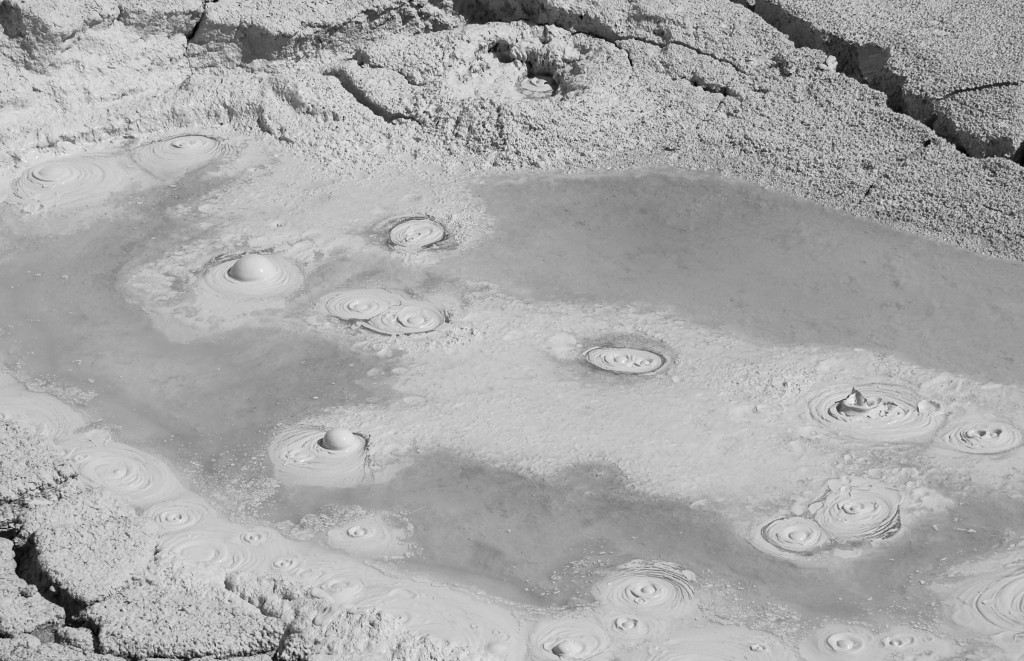

Artists Paint Pots

When little water is present within a hot spring, hydrogen sulfide gas — the cause of that rotten egg smell — converts to sulfuric acid, which breaks down any rock and clay. The result is a gooey mix of mud that gurgles and bubbles. Some research suggests that life first arose in similar mud pots.

Unnamed Fumarole

Without water or clay, an opening in the crust above the hot spot might just emit gases such as carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, hydrogen chloride and hydrogen sulfide. These so-called fumaroles (from the Latin “fumus” for smoke) are often accompanied by a hissing or a whistling sound.

The Black Pool

The last three super-eruptions have been in Yellowstone itself. During the most recent one, 640,000 years ago, a pillar of ash likely rose 100,000 feet, creating a haze thick enough to block the sun’s light before leaving a layer of debris across the West. But this wasn’t Yellowstone’s most powerful eruption. An eruption 2.1 million years ago was more than twice as strong and left a hole the size of Rhode Island.

Although many explorers first classified Yellowstone’s supervolcano as extinct, studies show that the basin is still changing. From 1976 to 1984, the caldera floor swelled about 7 inches. Then from 1985 to 1995 it sunk back down about 5.5 inches. The volcano is breathing.

So the question remains: Is it going to blow again? Scientists agree that some kind of eruption is highly likely at some point. But the odds of a super-eruption that will plunge the Earth into a volcanic winter are very unlikely — at least for the next 10,000 years.

—

All photos were shot by myself or my husband, Mike DiPompeo, during one of our many trips to Yellowstone and the Grand Tetons.