By Elizabeth Arakelian

November 9, 2015

The Illness

Baltimore native James Henry Carr III had a routine in high school: He would go to school, head to work at an oil company afterwards where he made good money, then walk straight to the projects where he would spend the remaining hours of the day selling drugs before school started up again.

“There were mornings when I went straight to school from selling dope,” recalled Carr. “Didn’t go home, wash up, change clothing, nothing. Went straight to school from hustling.”

Carr sniffed cocaine and used speed to stay awake long enough to maintain his schedule and he managed to graduate high school, even enrolling in community college. However, by the first semester, it was clear his hours were unsustainable and “something had to go,” he said.

“So what had to go? Whatever wasn’t making me no money. So school had to go,” said Carr.

Carr’s story is not unique in Baltimore where heroin is bought and sold as commonly as sugar at the grocery store. The proliferation of heroin use warranted Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake to convene a task force in October 2014 with the mission of developing tools to combat what is now referred to as the heroin epidemic.

The Mayor’s Heroin Treatment and Prevention Taskforce produced a report in July of this year that estimates that 18,916 people have used heroin in the past year in the city. But it is acknowledged by the report and those in the addiction treatment community, that these numbers are likely a large underestimation since illicit drug use is difficult to track.

While heroin use in Baltimore has thrust the city into the spotlight in recent years, illicit drug use is not unique to Charm City, evident by President Barack Obama’s visit to West Virginia earlier this week to discuss heroin treatment. The state of Maryland also convened the Maryland Heroin And Opioid Task Force And Coordinating Council in February to address the issue statewide. In 2014, Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin declared his state as having a “fully-blown heroin crisis” as the number of deaths from heroin overdose nearly doubled from 2013 to 2014.

“It is an epidemic that’s taking the country,” said Adrienne Breidenstine, Director of Opioid Overdose Prevention and Treatment at Behavioral Health System Baltimore. “It’s been a problem that’s been vexing Baltimore for many years, but other communities are seeing a stifling increase in their overdose deaths as well.”

In Baltimore, the areas with the highest number of overdose deaths include West Baltimore, Penn North, South Baltimore, and Park Heights.

Though the city’s sanctioned attack on the heroin epidemic has shed new light on the issue, it is not necessarily a new one.

“My experience growing up in Baltimore city is that the heroin addiction is not new,” said Selina Scipio, 43, a native of Sandtown. “It’s been around since the seventies, since I was a little kid and I’ve had several family members that were hooked on heroin.”

Despite being home to renowned intellectual and medical facilities, rampant heroin use has long contributed to Baltimore’s questionable reputation since the city’s seedier elements have often eclipsed its accomplishments

“As the city’s doctor, I have seen how heroin ties into the very fabric of Baltimore,” wrote Health Commissioner Doctor Leana Wen in the task force’s report. “It is impossible to separate heroin use from problems of poverty, violence, incarceration, homelessness, and ill physical and mental health.”

Karen Reese is the CEO of Man Alive Lane Treatment Center, an outpatient methadone clinic that treats more than 600 individuals with methadone and mental health services. Having been with Man Alive since the 1970s, Reese has witnessed first hand the evolution of heroin in the Baltimore City community, but is slow to hold it singularly responsible for the city’s poor reputation.

“I think the image of the city has been tarnished for a long time,” said Reese. “I think Baltimore has had a really bad image for a long time and I think it’s going to take us a while to actually convince people that it’s an okay city. If you want to know my opinion, I think many of the citizens suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder because there is a lot of violence and there’s a lot of anger and I don’t think there’s a lot of hope.”

It’s impossible to talk about heroin without talking about hope, or more often the lack of it. Losing hope is often instrumental in a person’s decision to use heroin, but having hope can also function as a shield against addiction.

“Getting hooked on heroin is easy,” said Scipio. “It’s easy to do that. It is a little bit of work to find a vision, to have hope. It does take a little bit of work, but it is 110 percent worth it in the long run.”

Carr has also experienced a revival of hope since seeking treatment for his heroin addiction at Man Alive. Ever since he dropped out of community college as a young adult the now 45-year-old Baltimore native said it has been in the back of his mind to return to school. Now, Carr is back in the classroom pursuing his associate’s degree in addiction counseling at Baltimore City Community College.

“My plans are not to stop there,” said Carr, who hopes to pursue a degree in the social sciences and eventually earn social work credentials so that he can become an addiction therapist himself. “The sky is the limit.”

The Diagnosis

James Henry Carr III remembers the exact day he decided to throw his life away. It was the day after his grandmother’s funeral.

Carr’s father passed away a week before he was born and his grandparents raised him since his mother, who had him at 17, was not capable of bearing the responsibility. His grandparents became everything to him so when they both passed away within months of each other from different forms of cancer, Carr wasn’t just sad. He was livid.

“I was lashing out,” recalled Carr. “I wanted to lash out because I wanted people to feel what I was feeling. I wanted people to feel the sadness and the rage all mixed up into one.”

That rage festered inside of him, but there was something that would numb it: heroin.

“When I was first introduced I was still in high school, 11th grade, junior year. I’ll never forget,” said Carr. “A couple so called friends of mine — which they were not friends for introducing me to heroin — offered me some in the bathroom.”

That fateful day in his high school bathroom was not Carr’s first exposure to drugs, though, as he was already selling them.

“I was groomed to be a dealer. That’s what I was groomed for,” said Carr. “ A lot of these youngsters on the street they are groomed from when they are younger. Either you are groomed to be a dealer, a hitman, or other things much, much worse. It depends on that child’s psyche.”

Carr’s psyche was severely damaged by the loss of his grandparents and his drug use worsened after their deaths. Eventually Carr was fully immersed in illegal activity beyond heroin use with a number of charges including robbery, assault, battery, attempted murder, and gun possession.

“It’s a list. I guess the average police officer would say it’s like a laundry list,” said Carr. “Altogether throughout my 45 years on this planet I have given the state of Maryland 12 years of my life.”

Carr used heroin for a total of 25 years. He traces his acting out back to the grief that unnerved him as a child when he lost his grandparents, citing his inability to properly grieve their passings as instrumental in the issues he faces as an adult. Carr suffers from depression, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

“Most of the years that I was out there committing all of these atrocious crimes and using heroin I truly believe in my heart that… if I was given the proper medication treatment and positive individuals in my life that I would not have ended up in prison for a lot of my life,” said Carr.

Carr is a client at Man Alive, a methadone maintenance facility where the philosophy is to not only treat the client’s addiction issues, but mental health as well.

“You can’t just treat one problem, you have to treat the whole person,” explained Man Alive’s CEO Karen Reese.

Man Alive was founded in 1967 and is the first medication assisted treatment program in the state of Maryland and the second oldest in the country. A physician and recovering addict, who had participated in a methadone study by the founders of methadone, founded the clinic with the aim of treating heroin addiction among Baltimore City residents.

Initially a small, volunteer based program, Man Alive has evolved since Reese joined in the early 1970’s and she has played an instrumental in shifting Man Alive’s focus to treat the whole person, and not just their addiction. The clinic now offers comprehensive mental health services with several counselors, a full-time psychiatrist, and licensed clinical professionals.

“It saved my life,” said Carr of his experience at Man Alive. “It really saved my life, because if I wouldn’t have came when I did, I would have ended up in prison or possibly dead on the street somewhere, in an alley somewhere, definitely.”

Though Man Alive treats the issue of addiction as a disease and not a bad habit, this perspective has historically been challenged by critics who see drug addiction as a choice. However, The city of Baltimore has also accepted that heroin addiction is a disease and is working to erase stigma attached to the topic of drug addiction so that those looking to stop using heroin can seek help without shame.

“We very much view substance use disorder as a disease,” said Adrienne Breidenstine, Director of Opioid Overdose Prevention and Treatment at Behavioral Health System Baltimore. “That is a big component of our education campaign and what we’re trying to do to raise awareness. Everything we’ve put out we’re trying to address the stigma.”

The stigma of which Breidenstine speaks includes perceptions by the public that substance use is indicative of a lack of willpower or poor moral standing.

“The stigma associated with substance use is that relapse is an utter failure when really it comes along with managing any disease,” said Breidenstine. “There are setbacks with managing any disease. It is just all part of the process and there are triggers that people need to respond to and they just don’t learn that until they relapse.”

“Relapse is part of recovery” is a common maxim expressed by those within the industry to combat the feelings of worthlessness that individuals battling addiction often feel when their recovery doesn’t go perfectly. Combining counseling with the addiction treatments is aimed at helping users achieve success not defined by their relationship to drugs. This is also a hallmark of the Mayor’s Heroin Treatment and Prevention Task Force’s treatment recommendations which state that “Effective treatment also requires mental health and physical health wrap-around services.”

Though Carr is still currently maintaining methadone treatments, his ultimate goal is to detox so that he can pursue his collegiate dreams and become an addiction counselor, something he only wants to do once he is completely clean. In the meantime, he has found a source of inspiration to motivate him through the hard times: his grandson.

The Treatment

It was seven years ago that James Henry Carr III received a call from his daughter that she was going into labor. More than a celebration, this was a turning point in Carr’s life because it was that day in the hospital that he decided to own up to his heroin addiction.

“While I’m sitting there waiting for the nurse to come out and get me and bring me in… I was sitting back reminiscing thinking about the day Ashley, my daughter, was born,” recalled Carr.

“Then the nurse finally calls my name: ‘Mr. Carr you can come in now.’”

It was entering the delivery room and getting to hold his grandson first, even before his daughter, that made Carr commit to a new start. Having loved his own grandparents so much, seeing his grandson for the first time, whom he affectionately refers to as his ‘little partner’ was a wake up call.

“The bond was there before he was born because of all of the love that my grandparents instilled in me,” said Carr of his grandson. “It’s ten fold with my little partner and I. Ten fold. Right then and there as I held that boy in my arms, I said, ‘Yeah, I’m getting myself together. I’m doing it. I’m doing it.”

Though Carr is on his way to fulfilling his goal of becoming completely clean, there are thousands of heroin users in Baltimore whose lives more closely resemble Carr’s prior to his grandson’s birth. That is something the Mayor’s Heroin Treatment and Prevention Taskforce hopes to change.

Something unique about the city’s heroin epidemic is that large masses of people are not only using the drug, they’re dying from it. With estimations of one person dying daily from overdoses the task force began distributing Naloxone even before publishing the report in July.

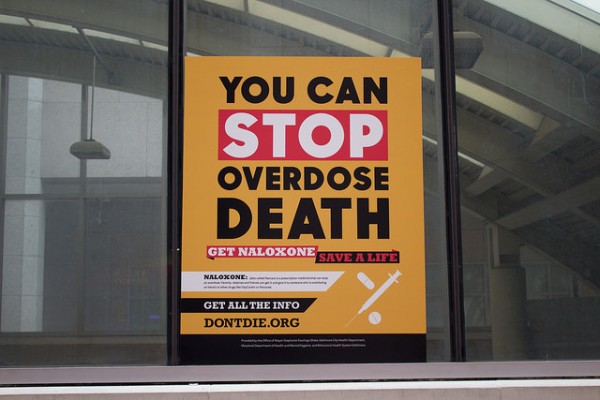

Baltimore City’s Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake convened a task force to address the growing heroin epidemic in the city the results of which included the launch of the less than subtle Don’t Die campaign targeted at getting the overdose drug Naloxone into the hands of residents who can help save lives. Photo by Elizabeth Arakelian

Naloxone is an overdose drug that prevents the receptors in the brain from binding with the chemicals of heroin, essentially extinguishes the user’s high. Naloxone can be administered to someone overdosing through an injection to the thigh muscle or through a spray to the nasal passage. The task force’s goal is for everyone, especially individuals in high risk communities who are likely to know someone who could overdose, to have Naloxone in their medicine cabinet or car so that they can help should they need to intervene. The City of Baltimore has been administering trainings almost everyday of the week at community events and churches and street teams are deployed to educated citizens with the hopes of equipping every citizen with Naloxone.

“We distribute Naloxone on the street and we try to put it in the hands of users,” said Adrienne Breidenstine, Director of Opioid Overdose Prevention and Treatment at Behavioral Health System Baltimore. “Anybody can do this. Anybody can save a life.”

Although relations between citizens and the Baltimore Police Department have been strained since the riots surrounding the death of civilian Freddie Gray just six months ago, Breidenstine said the force has been a “steadfast partner” in terms of fighting the heroin epidemic. Naloxone is in the hands of the Baltimore Police Department which has now incorporated Naloxone trainings into their academy curriculum and annual refresher.

“Our cops are using it. Just Tuesday one of our cops administered Naloxone to someone really early in the morning and saved a life,” said Breidenstine, who partly attributes the success of the partnership to the recently confirmed police commissioner’s experience in implementing the overdose drug in his previous department.

Although heroin related overdose deaths are staggeringly common, they are not overlooked.

“We are examining our overdose deaths in the city very closely,” said Breidenstine. “We have an overdose fatality review committee that meets monthly and looks at different cases. Those are really hard meetings because we’re looking at some really heart wrenching cases.”

A major concern of the task force’s has been finding a way to connect users with a treatment source. The task force has taken the initiative to streamline services, such as integrating two emergency phone lines into one crisis information and response line that is staffed 24/7 with trained and licensed clinical social workers.

The ultimate goal is to have access to care 24/7, something that the task force hopes it can eventually implement through a stabilization center that would function like an emergency room diversion location where people can find support services they need, sober up, and then be linked to more long term locations.

“The idea of treatment on demand is that if we’ve got a user on the street, they reach out to a provider and we should be able to get them a bed that day,” said Breidenstine, noting that that doesn’t always happen in the current system.

Though it is unforeseen how long it will take for the task force to actualize their treatment goals and see quantifiable success in ameliorating the city’s heroin epidemic, the overarching goal is clear: to one day, instead of counting deaths, count success stories like that of James Henry Carr III.