By Dale Isip

Milton Crooms sat towards the back of a long classroom with white walls, plastic tables and a whiteboard at the front. On the whiteboard were the handwritten letters and numbers of several algebraic equations, of which he and others were copying intensely. He leaned back in his chair.

“I can’t take much more school,” said Crooms, an adult education student at the Harlem YMCA.

Harlem has long been a neighborhood challenged with socioeconomic disparities, and the education gap is one of them. For decades, the area – when compared to the rest of New York City – has experienced lower outcomes in regards to graduation rates and academic achievement. Now, adult education programs in the area are working to reverse the gap.

“All the years that the teachers had told me they didn’t care,” said Crooms, “I step back into any classroom and I start to get real antsy and nervous. I was supposed to be educated, and I felt, if you all feel like that, I shouldn’t even be in a classroom.”

In the United States, there are over 30 million adults without a high school or equivalent diploma. This is about 9.4 percent of the entire country’s population. In Central Harlem, 20 percent of all residents do not finish high school, according a 2015 New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene report. This puts Harlem well below the national average.

“Most of our students are from within our vicinity,” said Kaitlyn Griswold, Program Coordinator for New Americans Welcome Center and Literacy Zone at the Harlem YMCA. She spoke of entry level student performance to the program. “We see most students score in the tenth and eleventh grade [levels], and eleventh being high.”

There has been a documented gap between the academic performance of high-income and low-income students, and the gap is growing larger. According to a national study, test scores between these income level students from 3rd grade through 8th grade have diverged by 40 percent over the last four decades, with high-income students coming out on top.

In Harlem, poverty and unemployment are relatively high when compared to the rest of the city. Whereas New York City has a poverty rate of 21 percent, Harlem has rate of 29 percent. Unemployment follows a similar pattern, with citywide unemployment at 11 percent, and Harlem at 13 percent. Though the racial proportions of the neighborhood have shifted in recent years, most adult education students are still Black or Hispanic.

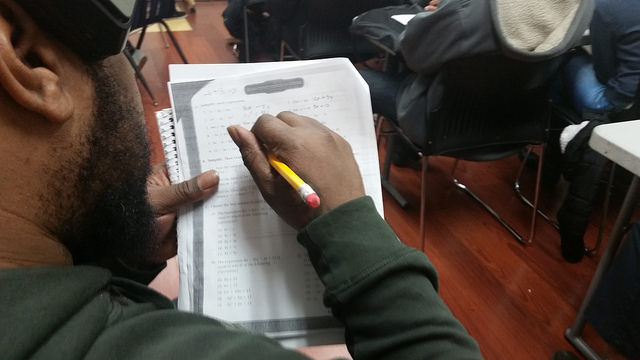

A student in the Harlem YMCA’s TASC program. Photo by Dale Isip.

David Perez, a Project Director at the Harlem Center for Education, spoke about his program’s demographics and employment status.

“The average age of students would probably be around 27 or 28,” he said. “It is mostly African American and Latino students. Some of them are working, some of them are not, some of them are on disability, so it varies.”

These disparities of income, even on a local level, can have an affect on academic performance, most notably in the city’s high school graduation rates. From the graduating class of 2005 to 2015, for example, Harlem’s school district – District 5 – has had a consistently lower percentage of students graduating high school in four years than in the wealthier areas of the city – like Staten Island’s District 31, for example. The disparities between these two districts have ranged steadily between 10 to 15 percentage points in the last five years, with Harlem’s district consistently on the lower end.

Griswold noted the students’ performance as one of the challenges her program faced.

“Keeping them engaged in it is really hard,” she said. “Mainly because they didn’t do well with traditional education … I guess maybe part of that coming from your whole life being told you can’t do it.”

For these reasons, there have been continuing efforts to spread word about adult education programs in Harlem, from the Harlem YMCA to Columbia University, as well other not for profit and public organizations.

“We’ve been around for more than 20 years,” said Sandy Helling, Associate Director of Columbia University’s Community Impact Program, “So a lot of people hear about us through word-of-mouth.”

In a neighborhood with over 7,000 units of public housing, Harlem is a high-density residential area that suffers from dilapidation and high crime – which has been on the rise in recent years. Some literacy programs work with the public housing agencies to seek potential students.

“We do try to work with the residents of the New York City Housing Authority, so they’ve actually selected us to be a zoned partner,” said Helling. “Residents of some of the local housing projects, once they say they’re interested in adult education, they will be referred to us.”

Adult education itself has changed in recent years. In January 2014, New York State replaced the General Equivalency Development (GED) with the Test Assessing Secondary Completion (TASC), a test that would serve as the state’s primary way to attaining a New York State High School Equivalency Diploma. Subjects on the test include reading, writing, social studies, science, and mathematics.

Before some students are ready to take the TASC, though, they must pass the Test for Adult Basic Education (TABE), a test that is normally given to students at lower grade reading levels and non-native speakers of English. The TABE is administered to measure basic math, reading, and language skills. Although native speakers of English usually move on to take the TASC, English as a second Language (ESL) students, for the most part, take the TABE for different reasons.

“The ESL students, 90 percent of them are immigrants, and their goals are not really to get their GED,” said Karen Poole, an TABE teacher at the Harlem YMCA. “Their goals are to read well enough where they can fill job applications, fill out forms properly, open up bank accounts, they want to know enough English to do that.”

Perez also spoke about economic motivations for adult education.

“We see education not only as a means for self development and growth, but also as a means for being competitive in today’s workforce,” said Perez. “Where even something as simple as a certificate or Associate’s degree can make a big difference, and the GED and TASC can make a big difference in these student’s lives.”

Some of the programs, like the Harlem Center for Education, are funded by state and federal grants, while others are funded privately or through universities. The amount of funding can sometimes limit what resources teachers have.

“We can’t give books to the students, but I make a lot of packets,” said Schindia Bidaisee, a TASC teacher at the Harlem YMCA, “I can print things out and make packets to give them, [but] I have to have it prepared and ready all the time…it is a little difficult in that way.”

Still, students found notable differences in teaching, and how teachers approach students.

“It’s the same work, but the only difference is that the teachers here are not going to tell you that they don’t care about your education,” said Crooms, “They’re not going to tell you that they’re only here for a check.”

“But she’s mad cool,” said Crooms of his TASC teacher Bidaisee. “I’ve never had a cool teacher in my life. She takes the time to really break down the work. Whatever you need, she’ll answer it for you, and explain it for you.”

Rafael Cruz was working as a security guard at the Harlem YMCA when he found out they were offering adult education classes. Although he had never finished high school, he did finish the TASC program a few years ago and was excited to do so. He is still working as a security guard and has a positive, though realistic, view of his experience.