by James Thorne

In the campaign against opiate addiction in Lackawanna County, government agencies at all levels are responding as the epidemic worsens. But politicians disagree over how much how much money is needed, and advocates worry that a lack of public funding and rising drug prices could stress an already fragile system.

In Pennsylvania’s Senate race, the candidates are divided over the July passage of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), which allocates $181 million of federal spending toward combating the heroin epidemic for 2017. Incumbent Republican Pat Toomey voted for CARA and has touted the bill as a win. Meanwhile, Democratic challenger Katie McGinty has attacked Toomey for opposing additional funding for the bill.

Deaths from heroin overdoses Lackawanna County totaled 69 people in 2015, double that of a year prior. The issue has become a rallying cry for Lackawanna County District Attorney Shane Scanlan, who recently launched the “Heroin Hits Home,” a campaign that promotes awareness through education and hosts an addiction helpline in an effort to reduce addiction rates. To pay for the program, Scanlan allocated money confiscated from drug-related arrests.

“I think it’s fantastic,” says Joe Kane, clinical administrator at Clearbrook Treatment Centers, who commends Scanlan’s efforts to lessen the stigma around heroin use.

But Kane worries that too much of the funding will serve the interests of pharmaceutical companies. Recently, Pennsylvania joined with 34 other states in suing pharmaceutical company Reckitt Benckiser for increasing the price of suboxone, a drug that has largely supplanted methadone as the standby for medically assisted treatment of opioid addiction.

According to Kane, a former addict who advocates an abstinence-based recovery model, much of the current funding is going toward medicated treatment programs that utilize drugs such as suboxone.

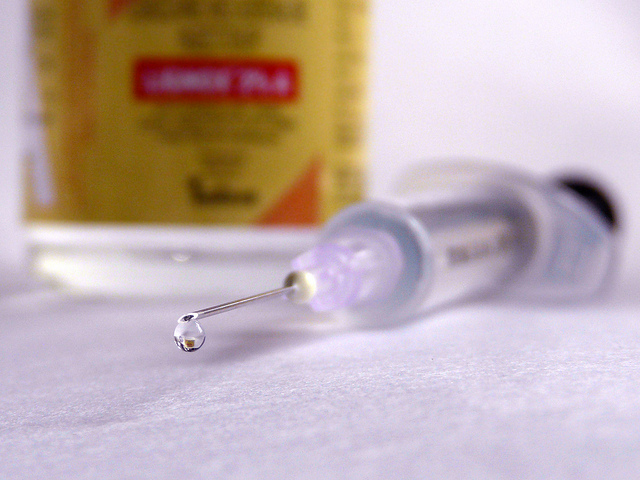

Similar criticism has been leveled at makers of naloxone, a 45-year-old drug that has become more expensive since it was first introduced. Narcan, a nasal-spray version of naloxone manufactured by Adapt Pharma, is used by the Scranton Police Department to reverse the effects of heroin overdoses.

Scott Constantini, director of behavioral health at the Wright Center in Scranton, also voices concern over the lack of funding for inpatient care units. “Long-term inpatient care is critical to curbing the problem,” Constantini says. The Wright Center currently only provides outpatient care.

Legislation such as CARA that restricts the prescription of opiates is a step forward, says Kane. But be believes such measures are likely to send more users to the streets in the near future, as opiate users who find their prescriptions unfilled begin to look elsewhere for the drug. This scenario is likely lead to additional demand for costly medication and treatment stays at inpatient facilities.

“A lot more money from the federal and state level is going to need to be allocated to address this issue,” Constantini says.

This summer, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf allocated $20.4 million to create a series of Centers of Excellence to provide treatment for opioid addiction, one of which is the Wright Center. Federal funding accounts for $5.4 million of that pot.

Legislation such as CARA aims to take some of the budgeting burden off of hard-hit states and counties, allowing programs such as Scanlan’s Heroin Hits Home and Wolf’s Centers of Excellence to expand in scope, and to allow for the creation of new programs. But as the Senate race makes clear, Democrats and Republicans are at odds over what those budgets should look like.

In her presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton has called for a $10 billion initiative to address alcohol and drug addiction. Regardless of the outcome of the election, it seems likely that the extent of federal funding for 2018 and beyond will hinge on whether one party is able to secure the White House and a Senate majority.